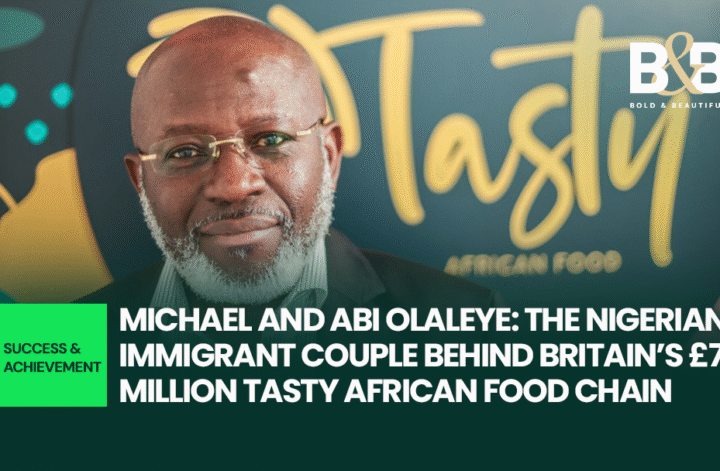

They began with two stainless steel pots and a Sunday congregation. Today Michael and Abi Olaleye run Tasty African Food, a West African restaurant chain pulling in about £7 million a year. The transformation reads like a recipe for scale: persistent labour, careful systems and a refusal to trade authenticity for trend.

Michael arrived in the UK with culinary instinct and little else. Abi carried recipes that had been refined at family tables back in Nigeria. Together they cooked for their church to raise funds. Those Sunday meals were simple and consistent. Neighbours started asking for takeaways. Local markets asked them to run a stall. Demand proved the original proof of concept.

Turning homemade success into a business required new skills. They learned food hygiene and commercial catering rules. They tracked costs meal by meal to understand margins. They wrote down recipes exactly so a team could replicate the flavours. A sense of craft moved from the kitchen in which they ministered to the kitchens where they would make a living.

Scaling meant choices. The Olaleyes focused their menu on dishes that could be produced well at volume while retaining flavour. They prioritised rice dishes, stews and grilled items that reflect West African tables. They developed sourcing relationships to secure key ingredients at reliable prices. Early suppliers were often small importers; over time those relationships matured into formal contracts.

Human systems mattered as much as ingredients. Michael and Abi built training routines that turned helpers into cooks. They created checklists for prep, cooking and plating. They introduced shift patterns that protected quality during the busiest hours. Staff retention rose as wages and job structure improved. For a business rooted in hospitality, that reliability became a competitive edge.

Finance followed operational discipline. Profits from pop-up events funded the first permanent site. Reinvested cash built a production hub to feed multiple outlets. The company chose modest, profitable expansion rather than rapid opening for the sake of visibility. That discipline is visible in the numbers: steady top-line growth that now reaches the seven-figure mark annually.

Branding stayed honest. Tasty African Food did not repackage the food as something it was not. The chain presented itself as West African food for regular people, not an exotic curiosity. Packaging, interior design and staff uniforms were selected to make customers comfortable and to signal quality without pretence. That clear identity helped attract a broad customer base beyond diasporic communities.

Community remained central. The couple continued to host events and to support local initiatives. Their restaurants became places where new arrivals could find familiar flavours and where wider audiences could discover West African cuisine. That role reinforced customer loyalty and created word-of-mouth momentum that paid dividends without large advertising budgets.

Operationally, the chain navigated challenges common to fast-growing food businesses: supply chain interruptions, staff churn and kitchen bottlenecks. The Olaleyes met those problems with pragmatic fixes. They diversified suppliers, formalised HR processes and invested in kitchen layout changes to improve throughput. Those adjustments kept service standards high even as footfall rose.

Ownership and governance evolved. Michael and Abi brought in a small number of trusted partners to provide capital and expertise as expansion accelerated. They retained control of culinary direction and company culture. The outside support helped professionalise accounting, legal compliance and property negotiations while leaving the founders to focus on food and people.

Looking ahead, the couple plans measured growth. The priorities are clear: maintain taste, protect margins and keep the workforce skilled. They are exploring wholesale and catering channels as ways to deepen revenue without over-stretching front-of-house operations. At every step they insist on preserving the recipes that started it all.

The deeper lesson lies in method and modesty. The Olaleyes turned a communal kitchen into a professional enterprise by paying attention to small, repeatable details. Their story shows how cultural labour becomes an economic asset when it is systemised, protected and scaled with care. For founders from immigrant backgrounds, their path offers a blueprint: start with community, build discipline around craft and grow with prudence,