‘Ẹlẹ́ṣin Oba: The King’s Horseman’ is Biyi Bandele’s Netflix adaptation of Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka’s play that tells the story of a Yoruba chief in British-occupied Nigeria whose plan to commit ritual suicide is resisted by the colonists.

Ẹlẹ́ṣin Oba: The King’s Horseman,” the last movie by Biyi Bandele- the Nigerian novelist, playwright and filmmaker, who died in August is described by Wall Street Journal (WSJ) as an elusive “something different”.

WSJ noted that Biyi Bandele’s “Half of a Yellow Sun” with Chiwetel Ejiofor and Thandiwe Newton was a successful adaptation of the Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie novel back in 2013, but “Horseman” is something else, a combination celebration of and elegy for cultural autonomy and something of a cheeky homage to African cinema.

ThisDay wrote that “Biyi Bandele, a transmedia storyteller and film maker transports the same themes of universal struggles of the will, culture clash, colonial subjugation, racial prejudice from text to screen while beaming lights on traditional Yoruba worldview and cosmology”.

Ẹlẹ́ṣin Ọba, the King’s Horseman is another adaptation of Wọlé Ṣóyínká timeless 1975 play, Death and the King’s Horseman, inspired by Dúró Ládipọ̀’s 1946 play, Ọba Wàjà (The King is dead).

Both plays are based on a real incident which unsettled the ancient city of Ọ̀yọ́ when a British civil servant prevented the sacrificial suicide of a town chief, Ẹlẹ́ṣin, who was ritually prepared to obey custom and follow his late king to the grave.

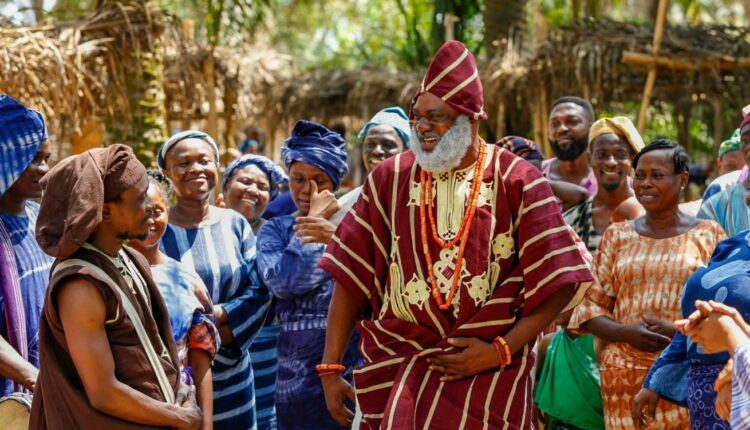

The film is based on the play “Death and the King’s Horseman” by Wole Soyinka (winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature), the story is based on actual events during World War II, when Nigeria was an occupied British colony. The eponymous horseman is a Yoruba chief who is about to commit ritual suicide; the people’s king has been dead a month and it is time for Elesin Oba (Odunlade Adekola) to follow his ruler into the afterlife (lest the king be left to wander and bring ill on his people).

Elesin, respected by all and eager to follow his prescribed destiny, is smitten on his last day by a young woman who is already affianced to the son of the tribe’s headwoman, Iyaloja (Shaffy Bello), who reluctantly agrees that Elesin can wed to the girl for one night—a send-off that no one but Elesin thinks is a good idea.

The British, as directed by the colonial magistrate, Simon Pilkings (Mark Elderkin), think suicide is a profoundly bad idea and set out to save Elesin’s life, even if it means killing people in the process.

From such displays of bicultural hubris, tragedies have blossomed from time immemorial, and the suggestion of a kinship between Mr. Bandele’s storytelling and that of the Western classical tradition is far from outlandish. Many African films are constructed as fables; to ask whether Mr. Soyinka’s play has been “freed” from its stage origins by Mr. Bandele’s camera would be the wrong question, because many of the great African directors, Nigerian and otherwise—the Senegalese Ousmane Sembène or Mali’s Abderrahmane Sissako, for example—have had little interest in “naturalism” as Westerners understand it and use their subjects the way Sophocles might have used his, partly as flawed humans and partly as vehicles for larger thematic elements within a drama.

As “The King’s Horseman” begins, this is what we get, the elucidation of tradition and spiritual belief through proclamation and symbolism. (The very air around the Yoruba village seems infused with the indigo being used to transform the place into a blue-dyed dream.) Only later is there anything like realism, and it parallels the descent of the story into the disruption of tradition, swept away in the unnavigable cross-currents of opposing cultures.

Mr. Soyinka said upon publication that his play was not intended as an anti-colonialist tract, and Mr. Bandele hasn’t made it one. Elesin is far more the target of his village’s anger and disappointment and that of his son, Olunde (Deyemi Okanlawon), than are the British—though Pilkings and his wife, Jane (Jenny Stead), are close to comically clueless, flouncing around their house in sacred native costumes confiscated during the arrest of a local.

They are fish entirely out of water—unlike Olunde, who has just returned from England as a doctor, his education facilitated by Pilkings, and who, perhaps predictably, is the character straddling cultures and representing the irreconcilable differences between peoples. Differences that first have to be perceived before they can begin to be mended.

One of the more ticklish conceits of “The King’s Horseman” is Pilkings and Elesin speaking to each other in their own languages and yet being perfectly understood. (The Soyinka play was written in English, but Mr. Bandele made his film largely in Yoruba.) In a film of grand acting, flamboyant colour, vaulting ambition and global conflict, the more slippery gestures contain much meaning.

Culled from WSJ

Mr. Anderson is the Journal’s TV critic