Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not just write novels. He cracked open history’s locked vaults, tore pages from the colonial playbook, and rewrote what it meant to be African.

To call Weep Not, Child his greatest book is not merely literary opinion, it is historical fact. First published in 1964, and the first major novel by an East African writer in English, Weep Not, Child signalled something rare and powerful: a Black African telling his story, in his own words, about his own people, from the inside. No translation needed.

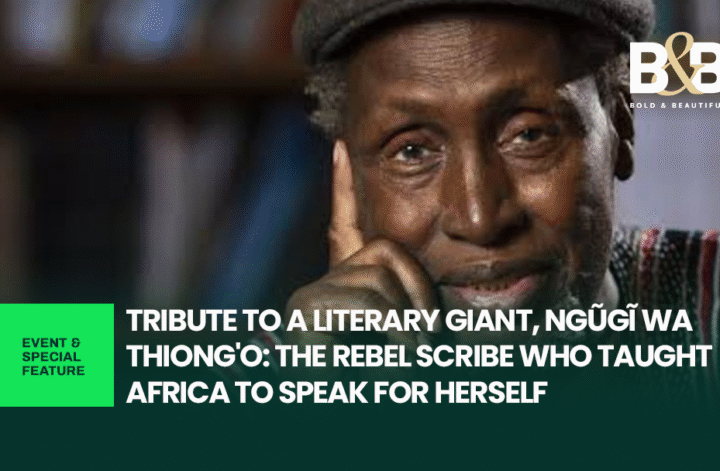

Today, as the world pays tribute to the Kenyan literary icon who passed on with ink-stained hands and a revolutionary mind, we revisit not only his body of work but the battles he fought with it. And won.

Ngũgĩ was never interested in polite fiction. His writing, gritty, beautiful, unrelenting, took on colonialism, capitalism, class, language, exile, and betrayal. He did not stand at a distance and describe the fire. He jumped in and burned.

A son of peasants, Ngũgĩ (born James Ngugi) understood the trauma of land seizure, the violence of missionary education, and the deep shame imposed by cultural erasure. Weep Not, Child, written while he was a university student, tells the story of Njoroge, a boy whose dreams are crushed by the Mau Mau uprising. It is not just a story of national upheaval, it is a story of generational pain.

But Ngũgĩ’s boldest move was yet to come. In 1977, after the publication of Petals of Blood, a scathing critique of post-independence corruption, he was imprisoned by the Kenyan government. His crime? Using fiction to tell the truth. From a jail cell, he wrote Devil on the Cross on prison toilet paper. In his native Gikuyu. It was his final break from English, which he came to see as a tool of imperialism.

In doing so, he challenged every African writer who followed him: Whose language are you loyal to? He said, clearly, “Ours.”

For Ngũgĩ, literature was never an escape. It was a weapon. A shield. A mirror. A call to arms.

He was not just a novelist. He was a cultural architect. A literary insurgent. An educator whose work was banned in his own country, even as it was being taught in universities abroad.

Even in exile, Ngũgĩ never detached. He wrote, taught, and stirred debate on every continent. From Harvard to Makerere, from London to Nairobi, his influence shaped syllabuses, transformed ideologies, and ignited movements.

Today, younger African writers, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Wole Soyinka, and even the late Binyavanga Wainaina, have walked through the doors Ngũgĩ kicked open.

But it all began with Weep Not, Child. That story of a boy trying to make sense of a broken country, written by a young man who had only just found his voice. A voice that would roar for decades.

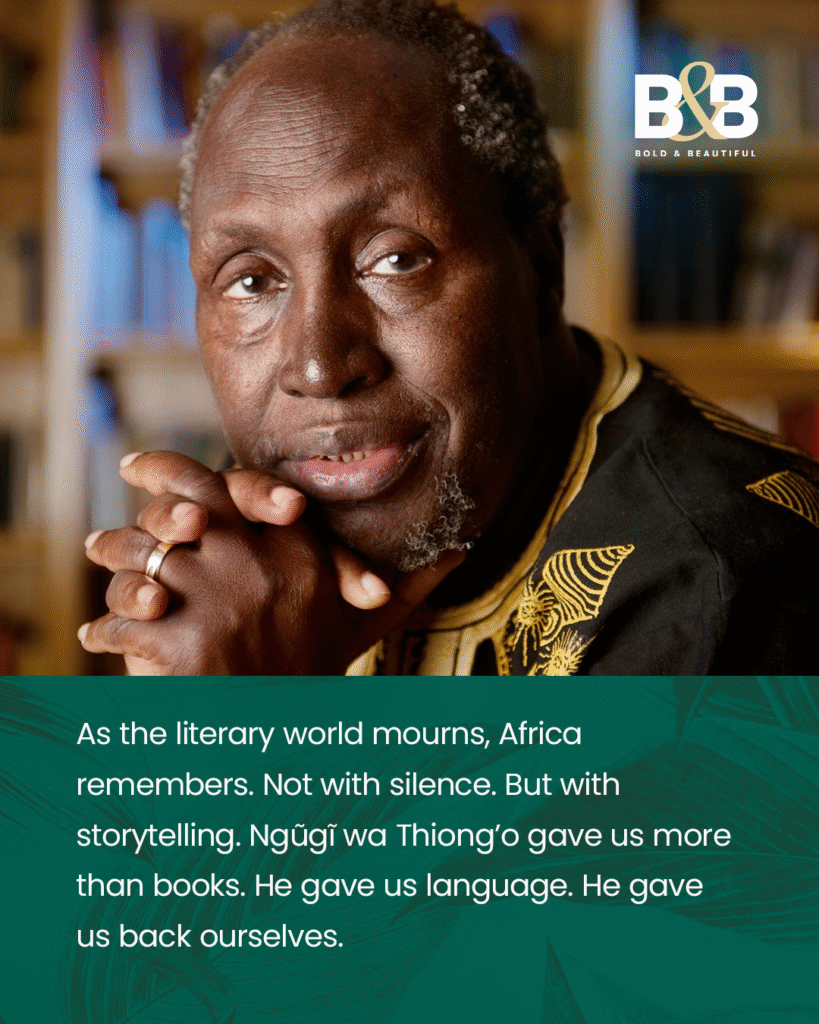

As the literary world mourns, Africa remembers.

Not with silence. But with storytelling.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o gave us more than books. He gave us language. He gave us back ourselves.